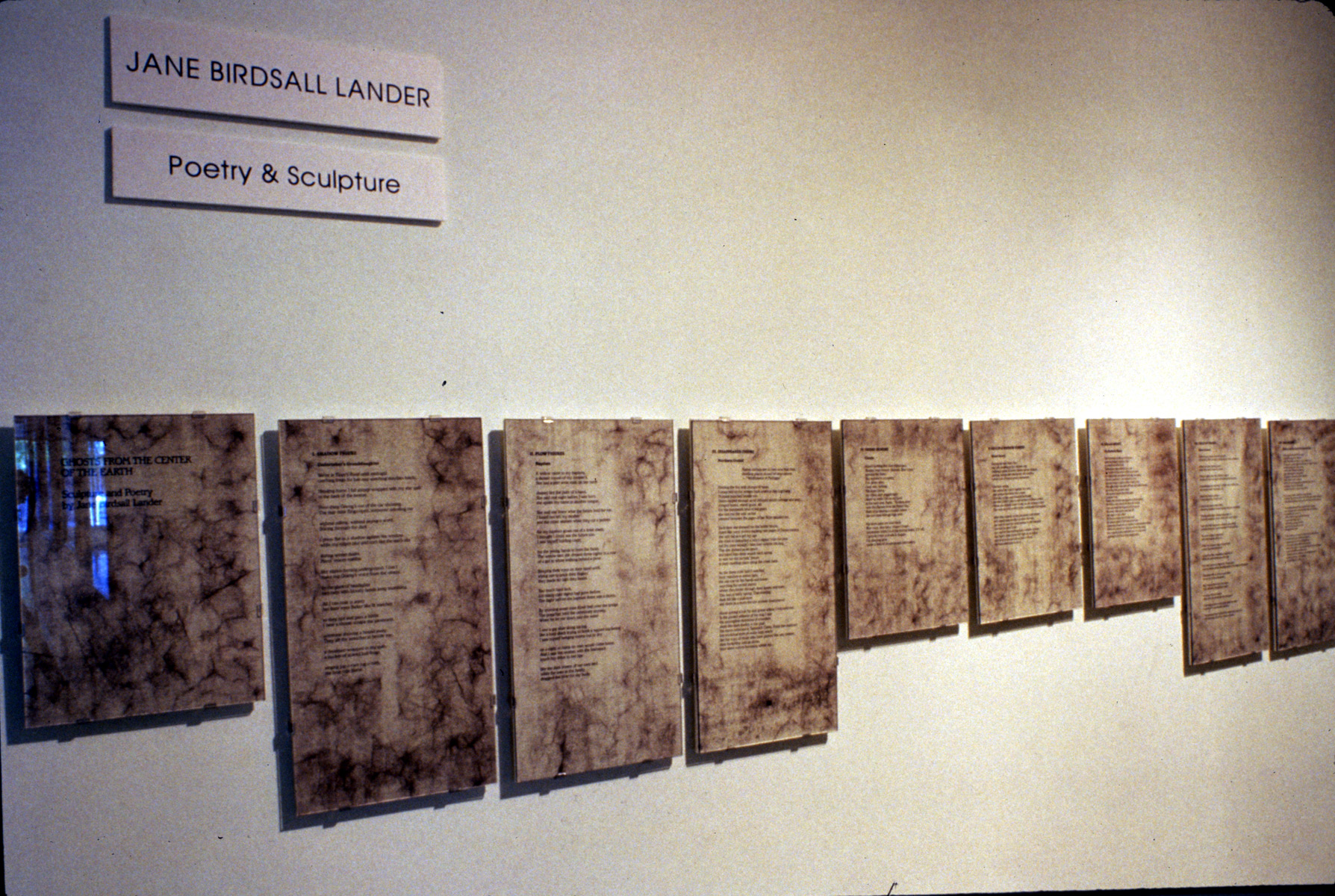

Installations: Poetry + Sculpture

Ghosts From the Center of the Earth

1993

Elliot Smith Contemporary Art, St. Louis, MO

Ghosts from the Center of the Earth is a site-specific installation incorporating poetry and objects. The human characters whose stories are given voice through the poems are composites and are as much a part of the rural landscape as are native wild flowers, wildlife, trees, rocks and the seasons themselves. The found objects I use are changed by time and human use and finally are worked on by me. My process is akin to bricolage, taking ideas and forms from multiple sources and recasting them in an individual vocabulary.

In the St. Louis Post Dispatch Carol Ferring Shepley states, “Jane Birdsall-Lander’s installation, titled Ghosts from the Center of the Earth, brings gasps from viewers. The room is beautiful, measured out with repetitive elements that seem both sacred and ordinary.”

Undertaker's Granddaughter

without asking, without saying a word.

Baptism

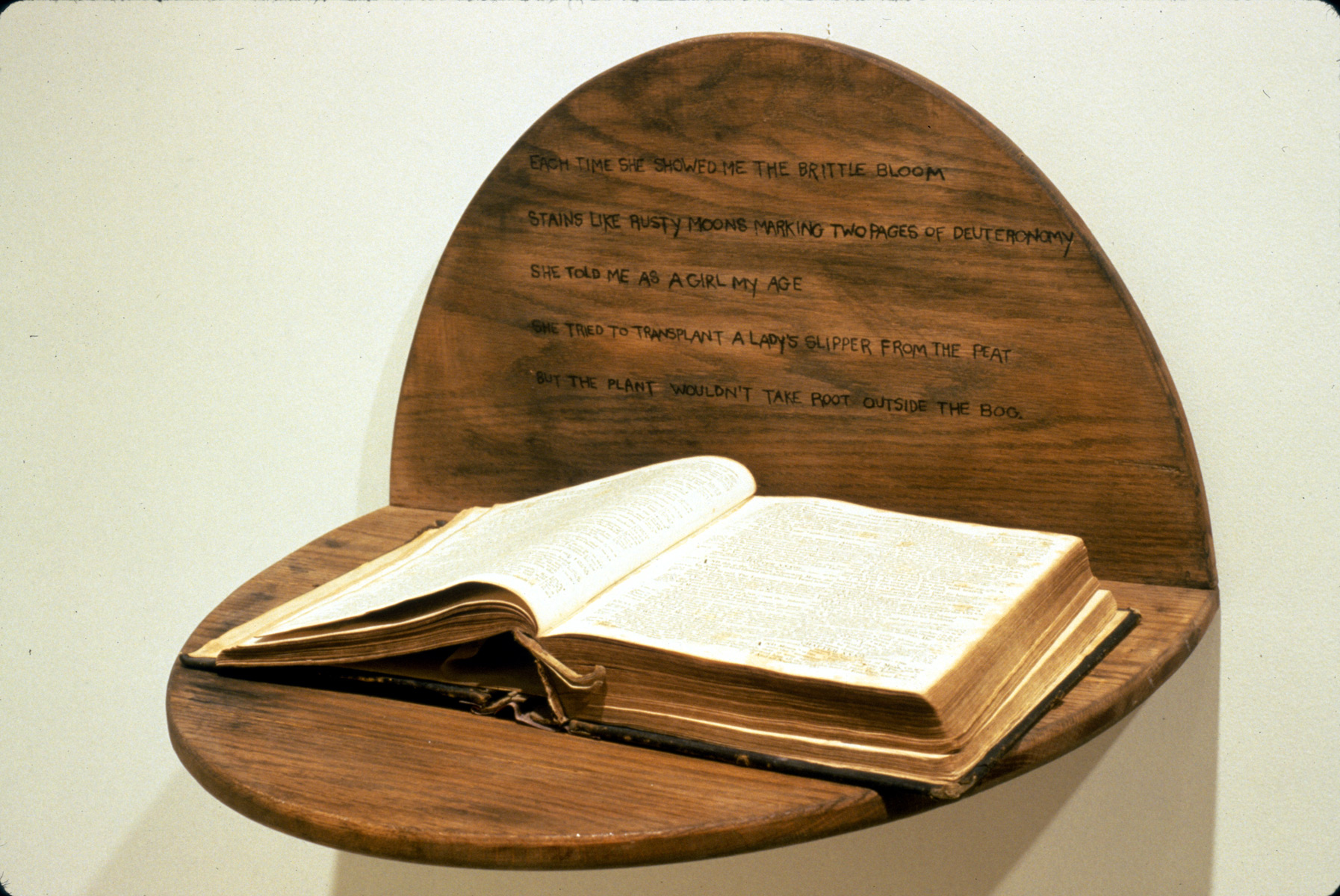

Northern Orchid

Alone among scrub fur and green willow

I followed her.

In the pooled stillness of the bog, I saw

the incomplete skeletons of crawdads

shine like stars buried in the peat,

the moon reflected in Tamarack Creek. From the

shadows the nocturnal eyes of snails kept watch

like the eyes of those who have

passed this way before,

their footprints cold as stone,

their silent voices humming within me.

Cicada

Blood Gravy

My Mother's Ghost

The foreman at the glove factory

gave my father a guinea hen

in trade for a fish knife.

Father kept that chicken as a pet

let it roost in the eaves of the tool shed.

At dusk when he walked through the gate

the hen danced in the dust at his feet

like my mother’s ghost after a hard frost.

The night father was laid off from the knife factory

he wrung the guinea’s neck.

We served supper late that night.

I couldn’t eat.

Father ate his biscuits dipped in blond gravy.

He told a story about his favorite hound,

how one night the dog ran off for good.

He never told me he was laid off

that night or any other.

He told me when he slit her neck

the guinea spun in the dust at his feet

splattering blood on my mother’s white washed fence.

When he pushed his chair back from the table

the scraping noise reminded me of a trap door

opening in the floor of an empty barn.

Beauty and Sorrow of an Unmade Bed

into the white envelope, smoothed and sealed

carved of marble, a grove of leafless granite trees

Dawn Funeral

my cousin steps to the edge of the grave.